Good guys and bad

What we need to battle America's enemies are the spirits of old! To keep the ideals of American freedom alive! With a man to lead them!

USA Comics

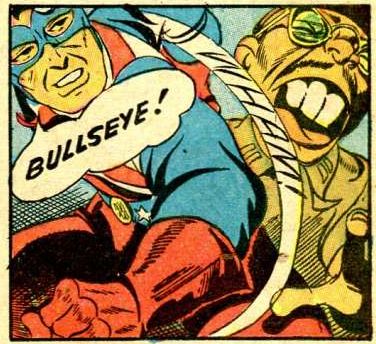

The heroes we have met so far are mostly regular guys, without any special powers apart from a quick mind, strong muscles, and an unwavering belief in American exceptionalism. Many wear a costume of some kind, even if it is just brown khakis with a symbol on the chest.

An example of a different kind of hero is the American Crusader. Not only does he possess superhuman powers (due to his atom smasher accident), but he also dresses in a red, white, and blue costume and does his fighting under a patriotic name. Although we have only met one guy like him so far, the American Crusader belongs to a whole class of patriotically themed superheroes suddenly appearing in comics books at this time.

Comic book superheroes before WWII devoted their time and energy to fighting murderous gangsters and even to some degree white-collar corporate crime. War was never a central theme; armed conflict took place on distant planets, or in the arid landscape of the American West, suppressing blood-thirsty Native American tribes. As war clouds gathered in Europe, America withdrew deeper into isolation. Most people wanted nothing to do with another European war.

It was against this background that the very first patriotically themed superhero appeared. Created by Harry Shorten and Irv Novick, and named the Shield, he debuted in Pep Comics #1, 1940. His costume consisted of a red suit and blue mask, and his massive chest as well as his boots and gloves were decorated with stars and stripes. Interestingly, his superpowers came from the costume itself, not from a freak accident. In other words, patriotism gave him superhuman powers.

The US was not in the war yet, and the Shield did not travel overseas to fight America's enemies, but stayed at home catching foreign spies. His real identity was Joe Higgins, "G-man extraordinary", who took his orders directly from J. Edgar Hoover of the F.B.I., and his job, as he saw it, was to shield the US government and the American people from harm. In many ways, the Shield is a truly isolationist superhero, devoted to fighting against vile foreigners coming to destroy the American way of life.

A great success, the Shield was soon followed, imitated even, by a whole host of patriotic comic book characters, among them Captain America, Minute-Man, Captain Battle, Uncle Sam, the Defender, the Conqueror, Spirit of 76, and Major Liberty, to name just a few. The mission of all these heroes was to encourage patriotism and to fight foreign spies and their sympathizers.

By the time President Roosevelt gave his speech in 1942, the war was raging throughout the world with America as one of the main belligerents. This gave the comics license to drop fictional names like Northland and Tradheim and create stories based on real countries and real events. At the same time, the comics willingly adopted several US propaganda goals: to demonstrate that the Allied cause was a just one, to portray the enemies as the baddest of bad guys, to shore up support for the war at home, and encourage Americans to be vigilant against spies and saboteurs.

The dastardly enemies of these superheroes quickly went from being foreign spies with a thick accent to actually being identified as Germans. The step was a small one and did not require much research from either writers or artists, as stereotypes already existed for the many different groups of people in the US. Everybody knew blacks were stupid, lazy and shiftless, and Native Americans cruel and backwards. Some of these stereotypes dated back to the very founding of the country, and additional ones were created as new waves of immigrants arrived at America's shores: the Irish were a belligerent quarrelsome lot and heavy whiskey drinkers to boot; the dishonest and money-obsessed Jews had noses so large they had trouble smoking or kissing; the Italians were organ grinders and fruit peddlers, hot-blooded and volatile; and the Germans slow, ponderous, and dull witted, loving their stinky sauerkraut and Limburger cheese.

This meant that coming up with ways to depict the enemy was easy. The only thing the comic book industry had to do was to update the stereotypes and fine tune them to fit the current situation.

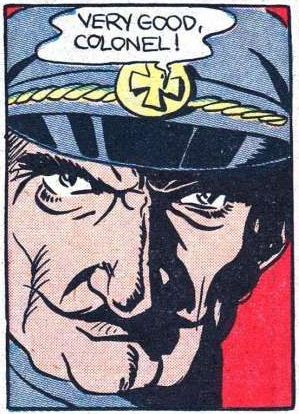

In Pep Comics #5 from June 1941, the German agents are still called by an invented name, but their accent is not to be mistaken. From a secret headquarters in Washington, DC, they plot to kill the Shield by sinking the passenger ship he travels on. But what if they sink the ship and the Shield is not on board? "Den ve haff lost notting except de lives of some vorthless Americans," the German leader argues. He seems to owe character traits to both the American stereotype and the caricature of a Prussian officer from WWI: He talks like a first generation German butcher in Brooklyn, while being depicted as an arrogant monocled Prussian aristocrat. His fellow officer in Amazing Man #21 fits the same mold, with his small WWI Kaiser Wilhelm mustache. But the bad guys are still not identified as Germans, however. In Amazing Man #22, the artist takes one step more in that direction by providing the bad guy with a swastika in his cap and dueling scars on his face. In Exciting Comics #15, the evil adversary is unequivocally a German and a Nazi, an amalgam of both stereotypes. His monocle represents the Prussian aristocrat, while his fat body, short-cropped hair, and bull neck, identify him as an immigrant German butcher.

Still, the comics often drew a line between Nazi Germans on one side and regular soldiers and citizens on the other. While Nazis were cruel and dishonest, haughty, evil, and aristocratic, the ordinary German adhered mostly to the old immigrant stereotype of being slow and dimwitted. In other words, despite the war, regular Germans were people, while the Nazis were beasts. Nazism was the enemy, not Germans in general. After all, Germans constituted the largest ethnic group of immigrants in America, and the comic book publishers had to be careful not to offend their readers. But once in a while, they did get hate mail when readers thought a comic book hero went too far in advocating war. Before Pearl Harbor isolationist feelings in America ran deep and strong.

America at war.

By the beginning of 1942, when America was at war with both Germany and Japan, much had changed. There was a different tone in the comic books. The comics were darker than before, more violent, and the enemies uglier.

In Air Fighters #3 Larry Wolfe battles the Nazis. Larry is an American pilot, who for some reason wears the head of a partially stuffed wolf as a balaclava, with his face showing through the gaping mouth. Inspired by his unusual headgear, he takes the name of Sky Wolf, and as a flying predator he is forever blowing enemy planes out of the sky. His German opponent also has a distinctive look, as much of his body has been replaced by steel plates. He is Baron von Tundra, also known as Half-Face or Half-Man. His names, as well as the steel plates, show us in a graphic way that the baron is no longer fully human. Sky Wolf might not look fully human either, but at least he can remove his wolf guise at will. Besides, he is the good guy.

Exciting Comics #18 features the Liberator, one of our flag-draped heroes with superpowers. When not a superhero, he is an ordinary bespectacled doctor, but turns into the Liberator by taking a swag of a bottle of not whiskey, but something called lamesis. Assisted by a giant cat, he fights Nazi saboteurs on American soil. These are presumably German-American, and look like regular citizens. The leader, however, has ugly and cruel facial features. He also wears a swastika tie, which is probably not the smartest thing to do if you are really serious about your sabotaging.

Just putting on a Nazi tie isn't enough for the home-grown Nazis in Daredevil #13. Dressed in a white robe like a member of the Ku Klux Klan, but with a large swastika on his chest, the leader solemnly proclaims: "Fellow-members of the German-American cult, you are sworn to eliminate the Democratic weaklings one by one." Merging Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan was a clever move, as both movements were racist and intolerant, similar in many respects. But also a little risky, as the KKK had been a large and popular organization just a few years before with at least four million members in America.

Still, the similarity between the KKK and the Nazis was pointed out in the comics several times. Putting the enemy in hooded KKK robes made him instantly racist and anti-democratic, without overly offending any German-Americans by depicting them with evil and cruel butcher faces. In Minute Man #3 the enemy again appears in Klan robes and masks, although green this time. They burn swastikas at night, and, like the Nazis, books. "Destroy those swinish drivelings! American democracy... BAH!" While they obviously hate books — all books it seems — they admire German culture: "American culture must make way for the iron kultur of der Fuehrer! Heil!" Lest any young reader should sympathize with book burning, we do get a glimpse of the leader's face under the mask, and it is hardly human, but snake like, with long sharp fangs.

It was only a matter of time before Nazis became superheroes, too. It always seemed a bit unfair when heroes with special powers battled enemies without, as there could be no doubt about the outcome, unless the hero's powers were somehow neutralized by for example something like kryptonite. In Master Comics #34, Captain Marvel Jr's adversary is a German called Captain Nazi, who is given the power to fly through the air by a French scientist turned traitor. Captain Nazi is a blond Arian with closely cropped hair and a dueling scar. He dresses in a tight-fitting green uniform à la Flash Gordon, with a large swastika on his chest. Strangely enough, Captain Nazi is depicted as an athletic and fit human, who is neither fat nor a monster, even though his deeds are despicable.

The same cannot be said of the Nazi on the cover of Pep Comics #34. In one claw-like hand he clutches a skull, while holding a sinister looking canister in the other, gassing a helpless female tied to the stone floor with iron hoops. His upturned nose is almost simian, his eyes under heavy brows bloodshot, his tongue snakelike, and his teeth sharp fangs. There is hardly anything human at all about this character.

The Hangman story in the same issue demonstrates another way of depicting a Nazi. Whereas the one on the cover looked like some nightmare beast, the one fought by the Hangman has no features at all — and yes, the Hangman is one of the good guys, despite his morbid name. The bad guy is Captain Swastika (they are all captains or barons, aren't they?) and he has no face, just a gray hood decorated with a red swastika covering his whole head. It is, however, not entirely clear if it is a hood or his real face. Judging from the artwork, it could be either. Anyway, in case the readers failed to notice his political preference despite all of this, his broad chest displayed a huge, black swastika in a white circle. The rest of his costume, by the way, seems like a motely mix of clothing articles bought at a second-hand store: ungainly work shoes, ill-fitting blue trousers, big yellow gloves, a red cape, and a fedora.

The cover of U.S. Jones #2 again shows a Nazi in a torture chamber setting. This one is more animal than man, too, with his green skin and a strangely enlarged mouth. Moreover, he is clearly a psychcopath who takes pleasure in administering pain to his victims. Yankee Comics #4 features a trio of Nazi saboteurs, looking more rat like than human, and in Zip Comics #27, Steel Sterling — Man of Steel — battles Baron Gestapo. Mr. Sterling is a typical hero of the time, a regular two-fisted, red-blooded American guy, except for his shorts, which look like they are bolted on, so maybe he is of steel after all. Baron Gestapo on the other hand, is a combination of the Prussian aristocrat stereotype and the animal Nazi. His blond hair is closely cropped, and he sports a monocle, while having pointed predator ears and sharp fangs. And on his chest is a blazing swastika, which again give rise to mental images of the Ku Klux Klan and their burning of crosses.

All of these examples are from 1942, and we could go on presenting examples of how the comics depicted Germans for a long time, but let us instead have a look at Japan, the other enemy.

The Yellow Peril.

Starting in the 1850s, stories spread in China about an American mountain of gold. These stories were inspired by the gold rush in California, and they sounded so convincing that many Chinese villages pooled their resources together and sent a handful of brave men across the Pacific in order to bring back the precious metal and lift everybody out of poverty.

Arriving in America, they found the gold rush more or less over, and besides, California gold fields were mostly barred to the Chinese and other minorities anyway. However, these young men discovered other economic opportunities, among them working for the Transcontinental Railway, which was being built at this time.

The Chinese were willing to work — and work hard — for less money than Americans. This caused friction and fears that they would take American jobs. In addition, the Chinese in general were met with hostility and scorn. Americans worried about opium dens and contagious diseases, and considered Asians barbarians and rapists.

Soon the laws were tightened, making it harder and eventually impossible for Chinese to enter the United States. Anti-Asian prejudices were already firmly set, not the least in popular culture, where Sax Rohmer portrayed Dr. Fu Manchu as conniving, sinister, and evil. The Chinese were the Yellow Peril, coming to replace white people.

Japanese immigrants began arriving in the US after the federal government banned Chinese immigration in 1881. They, too, worked for the railroad, and many began farming, causing resentment among American farmers who again feared the competition. Little distinction was made between Japanese and Chinese at this time, both nationalities represented the same malignant Yellow Peril.

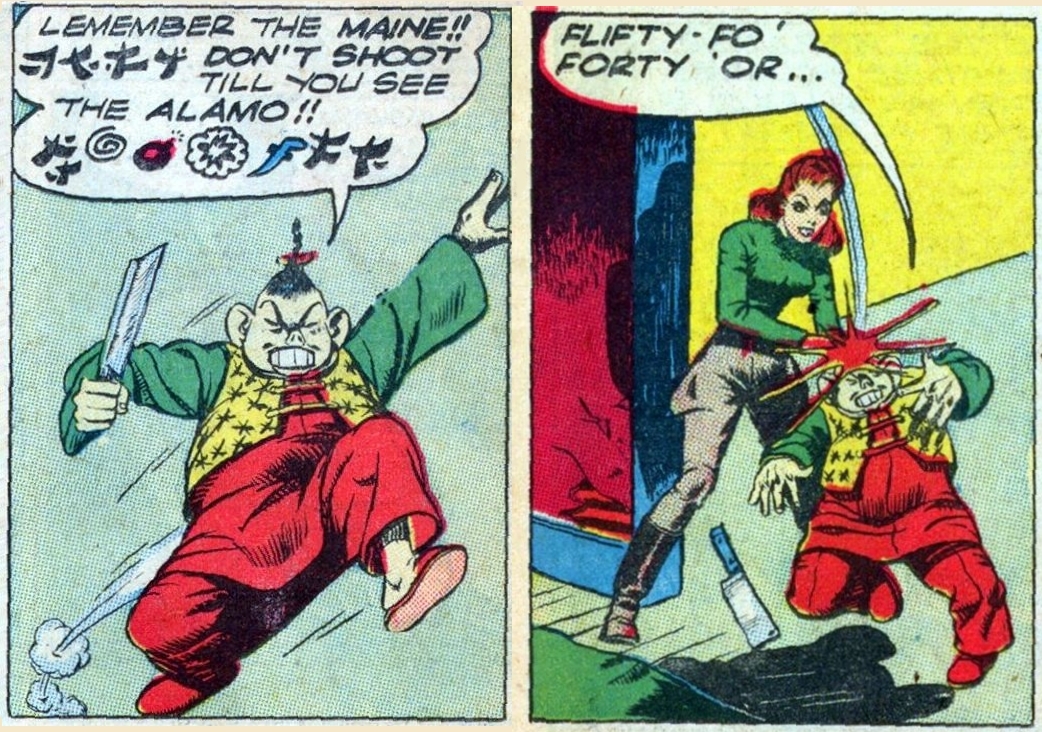

But war can create strange bedfellows. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, suddenly Nationalist China was an ally and had to be treated as such. Old prejudices die hard, however. The Chinese might not be sinister Fu Manchus anymore, but instead they defaulted back to another ingrained stereotype: the coolie; short and bowlegged, with bright yellow skin, bucked teeth, and a queue. And speaking in broken English, of course.

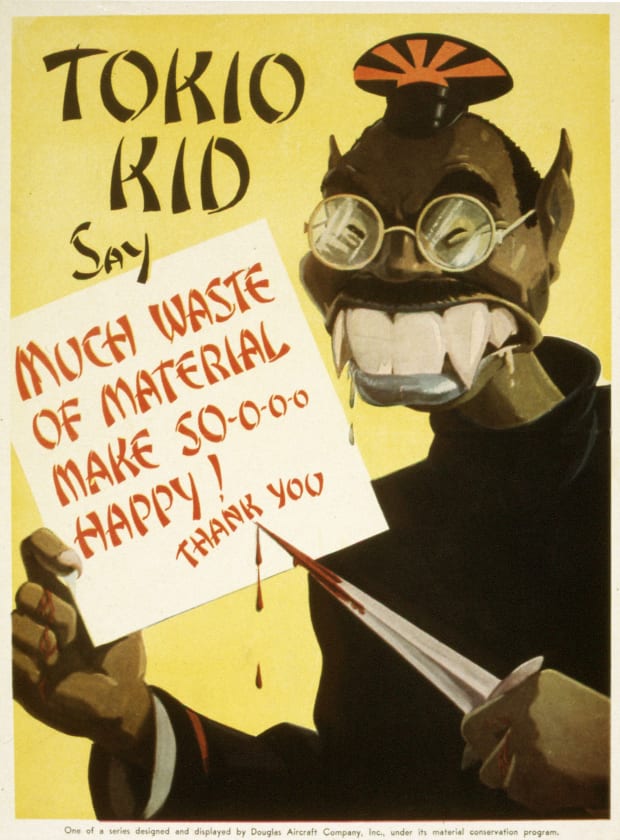

We have already seen a Chinese among the Blackhawks. His name is Chop-Chop, he is the team's mascot and chef, and does not wear the distinct Blackhawks uniform. Instead, he provides comic relief, being both clumsy and clownish. After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese rarely were pictured this way. Instead they all adhered to the Fu Manchu stereotype, being cruel and unfeeling. Plus treacherous, dishonest, and fanatical, buck toothed, near-sighted, and subhuman — more akin to animals than human beings.

Shield-Wizard Comics #7 from 1942 features the Shield, the flag-draped superhero defending American Democracy, this time in company with Dusty, his boy sidekick. By now, everything has come into focus. There is no longer any doubt about who the enemy is, or about his evilness. The half-naked Japanese brutes in this story are all depicted as ugly creatures, hardly human at all. And they are led by Fang, the ugliest of the ugly, with teeth matching his name.

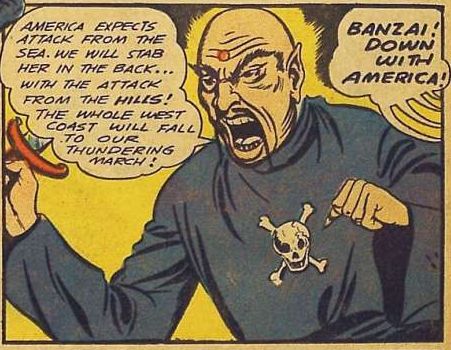

Captain Midnight, who has no superpowers but can fly like a squirrel, runs into a dangerous enemy in Captain Midnight #2 — a dastardly Japanese by the name of the Black Mikado. The Germans were easily mocked with the vons and baron titles. The Japanese not so much, probably because so little was known in America about Japanese society. No true Japanese would dare to call himself mikado, black or any other color, as this title was strictly reserved for the divine emperor. However, thanks to Gilbert & Sullivan's comic opera the term was familiar to westerners, although not fully understood.

The Black Mikado has claw like hands with long fingernails, a Fu Manchu mustache, large teeth, a skull emblem on his chest and a red circle on his forehead. The red circle might look like an Indian caste mark, but it more likely refers to the rising sun of the national Japanese flag. Like Captain Midnight, the Black Mikado has no superpowers, but that doesn't mean he is not formidable. He is described as a "fearsome, fanatical figure", and a "murderous Jap". The following sentence uttered by him reveals his mindset: "Black Mikado has struck, fools! He will strike again and again AND AGAIN... till America staggers like a blind, broken horse! HA, HA, HA, HA!"

In Cat Man #6 two stout marines, Bill and Wally, travel to Shanghai. Weapons shipped from the US to Nationalist forces in China have disappeared before reaching their destination, and it is up to Bill and Wally to solve the mystery. Taking a "stroll casually among the human dregs of the Orient," our two heroes walk into a trap. They are soon able to free themselves and at the same time discover that the missing weapons were thrown overboard and hauled in from the sea by the way of a "magnetic cable". The story is remarkable only in that "the human dregs of the Orient" with their yellow skin and animal features weren't even Japanese, but Chinese, and allies of the US at the time.

Crack Comics #23 features a story about Pen Miller. Mr. Miller is not a superhero, not even one of those regular two-fisted warriors. On the contrary, he is just a comic book artist, albeit one who solves crime on the side. Like every clever detective, he is assisted by a Dr. Watson. Except in this case, the sidekick is not a doctor, but a Chinese houseboy. The term "houseboy" has its roots in colonialism, and is clearly derogatory. The houseboy's name is Chop Chu (also derogatory), and even though he lacks the queue, he is definitely of the coolie type: small, with large teeth and a comical face. And his English needs some improvement: "Glacious! Submaline dunk and disappear!"

Trying to solve a mystery, Pen Miller and Chop Chu visit the New Nippon Casino, which unsurprisingly turns out to be an opium den run by a Japanese dragon lady. The dragon lady, a beautiful and deadly Asian woman, was another stereotype, widely appearing in comics. Originally she would be Chinese, but this story proved she could be Japanese as well. However, by the time the comic book was published all Japanese on the US West Coast had been "interned", which is a polite term for put in concentration camps, so there wouldn't have been any dragon ladies in New Nippon Casino, actually no New Nippon Casino at all.

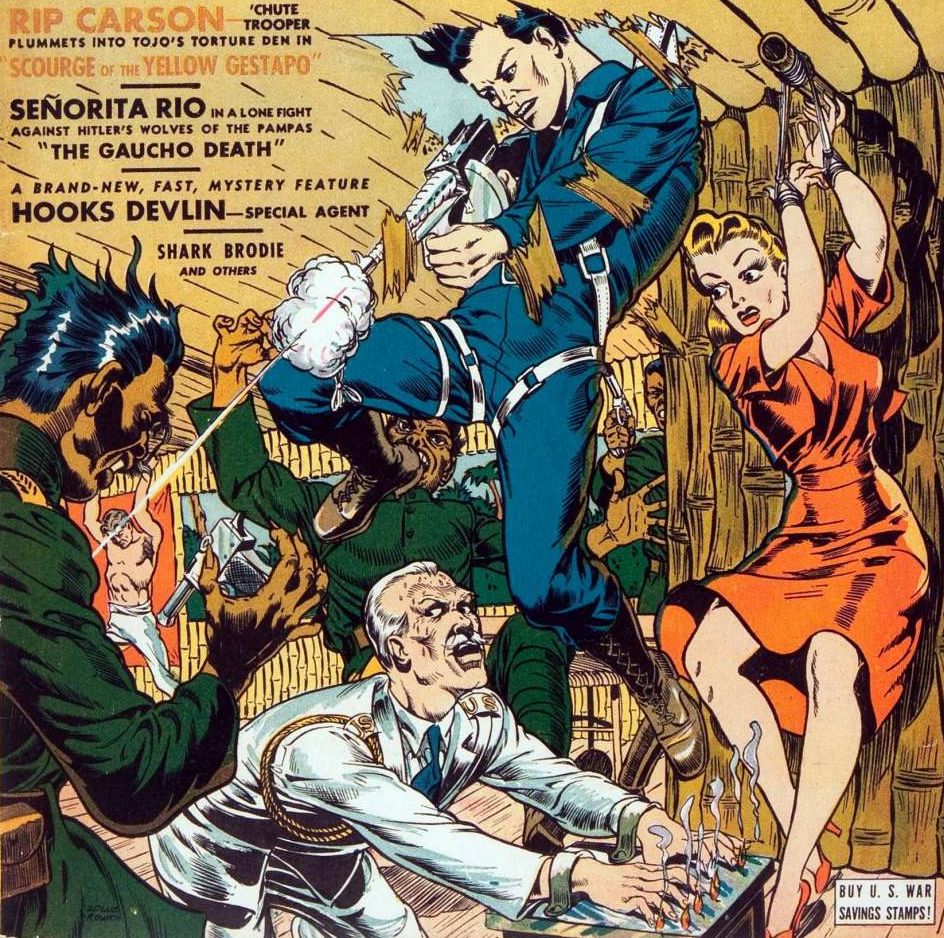

While there was a tendency to differentiate between German Nazis and Germans in general, no such distinction existed when depicting Japanese. They were all bad people, if human at all. To a man, Japanese soldiers were cruel and bloodthirsty. The cover of Fight Comics #20 shows a white man in American uniform being tortured, and a blonde, white woman with arms bound awaiting her turn. In the background is another white man obviously suffering after having gone through the same treatment. The torturers are regular Japanese soldiers, here depicted with brown skin and not the standard yellow. The cruel grins on their brutal faces tell us that they obviously take great pleasure in what they are doing. Fortunately, a white hero saves the day, as he comes crashing through the roof, blazing away with his tommy gun.

On the inside pages of the same book, we find a Shark Brodie adventure. Mr. Brodie is described as "a swash-buckling, freelance adventurer roaming the South Seas." Already on the first page, an unarmed, white man is shot in the back by Japanese soldiers, joyfully exchanging the following words: "White devil no escape." "Him dead." "May his cursed bones rot."

Among the lesser heroes, such as Shark Brodie, we also find Companions Three: Don, Spike, and Nifty, three American adventurers. The story in Master Comics #27 begins with the trio being shot by a Japanese execution squad. The shots having been fired, the Japanese officer is charge spits out: "SPPFFTT! Goodbye, Americans... you three pigs won't bother us ... AGAIN!" The trio didn't die, of course — heroes never do, even clumsy ones like these three always carry the day. We get a glimpse of two ordinary Japanese soldiers, described as "yellow fellows," who are "talking about some newly invented torture device to kill innocent people." In this case we may substitute "innocent" with "white." As the story ends, the Japanese are of course vanquished. And like all Japanese are supposed to do, they commit harakiri.

Master Comics#29 feature Minute Man fighting an evil scientist by the name of Dr. Fear. The doctor is a Frankenstein type of character; he even has a number of zombie-like henchmen. His great discovery is a gas that makes heroes afraid of their own shadow — the fumes of fear — with which he plans to destroy the US military and conquer America. Minute Man averts this by using his own secret weapon ... a gas mask. Who would have thought of that? As Dr. Fear suffers from his own gas, he admits to being Japanese, which is no big surprise either. His ugly face, coke bottle glasses, bucked teeth, and yellow skin told us that right from the beginning.

In Master Comics #33, Minute Man again has an encounter with Japanese gas canisters. These contain ordinary poison gas, however, manufactured on a tropical island, ready for use against American forces. By accident Minute Man discovers the hidden poison gas factory, and manages to alert America's heroes, the Flying Tigers, who shoot up the poison factory. A couple of things seem a bit odd in this picture. There really was an outfit called the Flying Tigers during WWII. However, it consisted of American freelance pilots in the service of Chiang Kai-shek, flying for the Nationalist Chinese. It was never an American unit employed in the Pacific. Besides, the machine guns of fighter planes would have been of limited use against a factory complex. Be that as it may, in this story all the Japanese, officers as well as men, have bucked teeth and ape-like features.

In Pep Comics #29, the Shield, assisted by his sidekick Dusty battles a menacing Japanese by the name of the Fang. He might be the same Fang they met before, but if so, he has changed quite a lot since then. The fangs are still there, but he is not half-naked anymore. Now he is dressed in a green costume with a large Japanese flag on his chest. However, he is as big and yellow as always. And his plans are big, too. He intends to assassinate the American president and "bring him back as a gift for our emperor. Ha, ha, ha."

The Web returns in Zip Comics #27, now battling the Black Dragon of Death, described as a "sinister, mocking, ruthless agent of the treacherous Japs." The Black Dragon of Death is clearly modeled on the Fu Manchu stereotype. He sports the same kind of drooping mustache, the yellow skin, the sharp fangs, and long nails on claw-like fingers. As if this isn't enough to portray him as an evil Oriental, he also has "venomous eyes". The Black Dragon of Death seems to thrive in torture chambers, surrounded by heartless helpers, almost as evil as he. One thing sets him apart, though. He has the somewhat effete habit of always carrying a bottle of perfume, constantly spraying himself, especially after brutally murdering someone. The Black Dragon of Death operates out of Chinatown, where nobody suspects he is Japanese. In the Web he has met his match, however, and the "yellow monkeys" (his words) end up biting the dust. Racism ran deep even among professors of criminology.

These examples are from 1942, and they are just the tip of the iceberg. There was a tendency to depict Germans in general move favorably than their Nazi compatriots. But the Japanese were always shown in the worst and most racist way.

Government propaganda.

During WWII paper for printing was a rationed commodity. At the same time, there seemed to be an insatiable demand for comic books, forcing publishers to reduce the number of pages in order to maintain a high print run. Since comic books were so popular, it was only natural that the US government kept a vigilant eye on the content. Besides, comics presented an unparalleled opportunity of reaching a vast and uncritical audience. And the audience was not just kids, as polls during the war revealed that one in two servicemen also enjoyed reading comics.

This is why the government did more than just keep an eye on the comics. In fact, it took an active role in creating the books through an organization called the War Writers' Board, WWB for short. The WWB was set up in such a way that it looked like an independent organization run by volunteers, but in reality it was funded by the US government, which also directed its work. The WWB was under the umbrella of the Office of War Information (OWI), and as we know, in war there is precious little information, but no end to the propaganda.

The government could not force publishers to join the WWB, but most still did voluntarily. In wartime, it was seen as a patriotic duty. Besides, being in good standing with the government might ensure an increased ration of paper, which was as good as extra money in the pocket. In this way, the comic book industry willingly became a part of US government propaganda. No pressure was needed, as the interests of the publishers and the propaganda office were identical. The government wanted heroics, and the public did the same. In fact, propaganda sold like hotcakes.

WWII became the "good war", and comic books did their best to portray it as such. Anything negative that might hurt the war effort had no place on the comic pages.

The way the WWB created comic book propaganda was through its Comics Committee. The name might sound dusty and dull, but for the members of the committee it was anything but. They did not just review material sent them, but came up with ideas for story lines, language and expressions, even new heroes. In other words, the US government was involved on every level of the comic book industry. And since none of this happened in the open, there was no holding back. On the contrary, few if any, governments has produced anything as hateful as American comics during WWII.

Our sample of enemy depictions from 1942 looks bad, but worse was to come. The WWB often returned drafts to publishers on the grounds that the story or artwork was not anti-German or anti-Japanese enough. By 1944, the board made clear that the enemy was not just Nazis, but the German nation in its entirety. Creating comics attacking Nazis only was wrong and a waste of time. All of Germany was responsible for Nazi crimes against humanity. The country and its citizens were unable to change, and would forever be anti-democratic, cruel, and warlike. Any presentation of Germans should induce hatred in the reader, in order to help the Allied war effort and put an end to Germany once and for all.

Despite all this free propaganda, the OWI often complained about the comics. Their view was that writers and artists did not understand what the war was all about. The narrative that America, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union were allies in a common fight against Nazism was rejected. Instead, the comics should demonstrate that Americans do it alone. The US needed no allies; at most, America was assisted by subordinates like Britain and the occasional local resistance movement. The Soviet Union, which bore the brunt of the fighting during WWII, was not to be mentioned. In this beyond jingoistic (and plain wrong) thinking, we find the roots of how Norwegians were depicted, and why President Roosevelt's speech had so little effect.

According to the OWI, Germany and Japan were aberrant societies, and Japan definitely the worst of the two. Not only had the Japanese inflicted a terrible wound on America at Pearl Harbor, but they also represented the Yellow Peril. Consequently, the OWI demanded race war in the Pacific. The Japanese people needed to be exterminated. And this was not just propaganda found in comic books, but a widely held belief. According to the US Army Air Force, the entire population of Japan — every woman, man, and child — was a "proper military target". Consequently almost every major city in Japan was indiscriminately showered with fire bombs, explosives, and napalm from the air. And finally, Hiroshima and Nagasaki — targets without military value, but full of people — were leveled by American atom bombs. An unspeakable crime, made possible in part by comic books.